Caporegime

I would like to dedicate today to Primo Levi, whose books moved me deeply when I was younger. May he rest in peace.

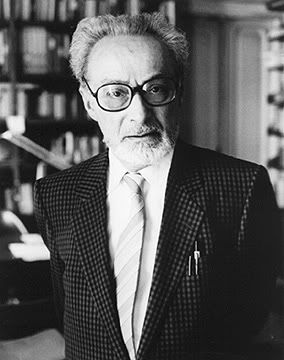

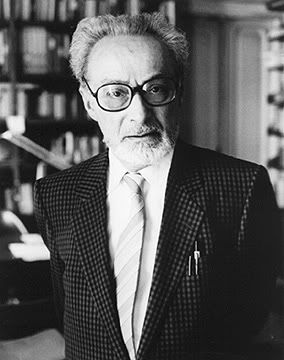

Primo Michele Levi (31st July1919 to 11th April 1987) was a Jewish-Italian chemist, Holocaust survivor and author of memoirs, short stories, poems, essays and novels.

He is best known for his work on the Holocaust, and in particular his account of the year he spent as a prisoner in Auschwitz, the death camp in Nazi-occupied Poland. If This Is a Man (published in the United States as Survival in Auschwitz) has been described as one of the most important works of the twentieth century.

Early life

Levi was born in Turin on July 31, 1919 at Corso Re Umberto 75 into a liberal Jewish family. His father Cesare worked for the manufacturing firm Ganz and spent much of his time working abroad in Hungary, where Ganz was based. Cesare was an avid reader and autodidact. Levi’s mother Ester, known to everyone as Rina, was well educated, having attended the Instituto Maria Letizia. She too was an avid reader, played the piano and spoke fluent French. The marriage between Rina and Cesare was arranged by Rina’s father. On their wedding day, Rina’s father, Cesare Luzzati, gave Rina the apartment at Corso Re Umberto where Primo Levi was to live for almost his entire life.

In 1921 Anna Maria, Levi's sister was born; he was to remain close to her all of his life. In 1925 he entered the Felice Rignon primary school in Turin. A thin and delicate child, he was shy and thought of himself as being ugly, but he excelled academically. His school record includes long periods of absence during which time he was tutored at home at first by Emilia Glauda and then by Marisa Zini, daughter of philosopher Zino Zini. Summers were spent with his mother in the Waldensian valleys south-west of Turin where Rina rented a farmhouse. His father remained in Turin partly because of his dislike of the rural life, but also because of his infidelities.

In September 1930 he entered the Massimo d'Azeglio Royal Gymnasium a year ahead of normal entrance requirements. In class he was the youngest, the shortest and the cleverest as well as being the only Jew. For these reasons, he was bullied. In August 1932, following two years at the Talmud Torah school in Turin, he sang in the local synagogue for his Bar Mitzvah. In 1933, as was expected of all young Italian schoolboys, he joined the Avanguardisti movement for young Fascists. He avoided rifle drill by joining the ski division, and then spent every Saturday during the season on the slopes above Turin.

As a young boy Levi was plagued by illness, particularly chest infections, but he was keen to participate in physical activity. In his teens Levi and a few of his friends would sneak into a disused sports stadium and conduct athletic competitions.

In July 1934 at the age of 14, he sat the exams for the Massimo d'Azeglio liceo classico, a Lyceum (sixth form) specialising in the classics and was admitted that autumn. The school was noted for its well-known anti-Fascist teachers, amongst them the philosopher Norberto Bobbio, and for a few months Cesare Pavese, also an anti-Fascist and later to become one of Italy's best-known novelists. Levi continued to be bullied during his time at the Lyceum although he was now in a class with six other Jews. On reading Concerning the Nature of Things by Sir William Bragg it was during this time that Levi decided that he wanted to be a chemist. Levi matriculated from the school in 1937 despite being accused of ignoring a call-up to the Italian Royal Navy the week before his exams were due to begin. As a result of this incident, and possibly some antisemitic bias in the marking, Levi had to retake his Italian paper. At the end of the summer he passed his exams and in October he enrolled at the University of Turin, to study chemistry. The registered intake of eighty hopefuls spent three months taking lectures in preparation for their colloquio or oral examination when the eighty would be reduced to twenty. The following February Levi graduated onto the full-time chemistry course.

Although Italy was a Fascist country, and antisemitism took place, there was little real discrimination towards Jews in the 1930’s. As Italy was historically one of the most assimilated Jewish societies, the gentile Italians, up until the outbreak of hostilities, either ignored or subverted any racial laws which they saw as being imposed by the Germans. This all changed in July 1938 when the Fascist government introduced racial laws which, amongst other things, prohibited Jewish citizens from attending state schools. Jewish students who had begun their course of study were permitted to continue them, but new Jewish students were barred from entering university. It was therefore fortuitous that Levi had matriculated a year early, as he would not otherwise have been permitted to take a degree.

In 1939 Levi began his love affair with hiking in the mountains. His friend Sandro Delmaestro taught him how to hike and they spent many week-ends in the mountains above Turin. Physical exertion, the risk and the battle with the elements here supplied him with an outlet for all the frustrations in his life. In June 1940 Italy declared war against Britain and France, and the first air raids on Turin began two days later. Levi’s studies continued during the bombardments, and an additional strain on the family was imposed when his father became bedridden with bowel cancer.

However because of the new antisemitic laws, and the increasing intensity of prevalent Fascism, Levi had difficulty finding a supervisor for his graduation thesis which was on the subject of Walden inversion, a study of the asymmetry of the carbon atom. Eventually taken on by Dr. Nicolo Dallaporta he graduated in the summer of 1941 with full marks and merit, having submitted additional theses on X Rays and Electrostatic Energy. His degree certificate bore the remark, "of Jewish race". The racial laws prevented Levi from finding a suitable permanent position after he had graduated.

In December 1941 Levi was approached and clandestinely offered a job at an asbestos mine at San Vittore. The project he was given was to extract nickel from the mine spoil, a challenge he accepted with pleasure. It was not lost on Levi that should he be successful he would be aiding the German war effort, which was suffering nickel shortages in the production of armaments. The job required Levi to work under a false name with false papers. In March 1942 while he was working at the mine Levi’s father died.

In June 1942, due to the deteriorating situation in Turin, Levi left the mine and went to work in Milan. He had been recruited through a fellow student at Turin University who was now working for the Swiss firm of A Wander Ltd on a project to extract an anti-diabetic from vegetable matter. He could take the job because the racial laws did not apply to Swiss companies. It soon became clear that the project had no chance of succeeding, but it was in no one's interest to say so.

In September 1943, after the Italian government under Marshal Pietro Badoglio signed an armistice with the Allies, the former leader Benito Mussolini was rescued from imprisonment by the Germans and installed as head of the Italian Social Republic, a puppet state in German-occupied northern Italy. Levi returned home to Turin to find his mother and sister having taken refuge in their holiday home La Saccarello in the hills outside Turin. They all then embarked to Saint-Vincent in the Aosta Valley where they could be hidden. Being pursued by the authorities they moved up the hillside to Amay in the Colle di Joux. Amay was on the route to Switzerland that was followed by Allied soldiers and refugees trying to escape the Germans. The Italian resistance movement became increasingly active in the German-occupied zone. Levi and a number of comrades took to the foothills of the Alps and in October joined the liberal Giustizia e Libertà partisan movement. Completely untrained for such a venture, he and his companions were quickly arrested by the Fascist militia. When told he would be shot as a partisan, he confessed to being Jewish and was then sent to an internment camp for Jews at Fossoli near Modena. Primo Levi's writings archived at Yad Vashem indicate that that as long as Fossoli was under Italian, rather than Nazi German control, he was not harmed. "We were given, on a regular basis, a food ration destined for the soldiers," Levi's testimony stated, "and at the end of January 1944, we were taken to Fossoli on a passenger train. Our conditions in the camp were quite good. There was no talk of executions and the atmosphere was quite calm. We were allowed to keep the money we had brought with us and to receive money from the outside. We worked in the kitchen in turn and performed other services in the camp. We even prepared a dining room, a rather sparse one, I must admit."

Auschwitz

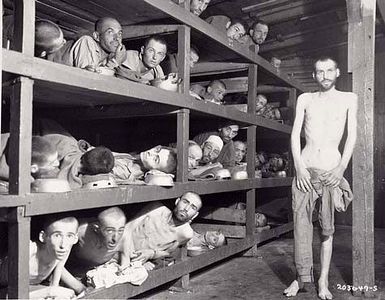

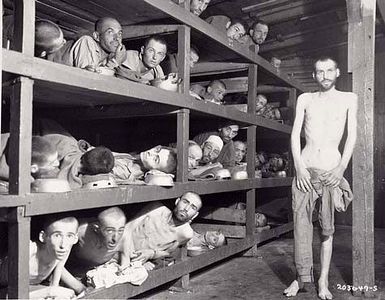

When Fossoli fell into the hands of the Germans, the Jews were rounded up for deportation. On February 21, 1944, the inmates of the camp were transported to Auschwitz in twelve cramped cattle trucks. Levi spent eleven months there before the camp was liberated by the Red Army. Of the 650 Italian Jews in his shipment, Levi was one of only twenty who left the camps alive. The average life expectancy of a new entrant was three months.

Levi knew some German from reading German publications on chemistry; he quickly oriented himself to life in the camp without attracting the attention of the privileged inmates; he used bread to pay a more experienced Italian prisoner for German lessons and orientation in Auschwitz; and he received a smuggled soup ration each day from Lorenzo Perrone, an Italian civilian bricklayer, imprisoned as forced labourer. His professional qualifications were also useful: in mid-November 1944 he was able to secure a position as an assistant in the Buna laboratory that was intended to produce synthetic rubber, thereby avoiding hard labour in freezing outdoor temperatures.

Shortly before the camp was liberated by the Red Army, he fell ill with scarlet fever and was placed in the camp's sanatorium (camp hospital). In mid-January 1945 the SS hurriedly evacuated the camp as the Red Army approached, forcing all but the gravely ill on a long death march that led to the death of the vast majority of the remaining prisoners. Levi's illness spared him this fate.

Although liberated on 27 January 1945, Levi did not reach Turin until 19 October of that year. After spending some time in a Soviet camp for former concentration camp inmates, he embarked on an arduous journey home in the company of former Italian prisoners of war from the Royal Italian Army in Russia. His long railway journey home to Turin took him on a circuitous route from Poland, through Russia, Romania, Hungary, Austria and Germany.

What drove Levi to write was a desire to bear witness to the horrors of the Nazis' attempt to exterminate the Jewish people. He read many accounts of witnesses and survivors and attended meetings of survivors, becoming in the end a symbolic figure for anti-fascists in Italy.

Levi visited over 130 schools to talk about his experiences in Auschwitz. He was shocked by revisionist attitudes that tried to rewrite the history of the camps as less horrific, what is now referred to as Holocaust denial. His view was that the Nazi death camps and the attempted annihilation of the Jews was a horror unique in history because the aim was the complete destruction of a race by one that saw itself as superior; it was highly organized and mechanized; it entailed the degradation of Jews even to the point of using their ashes as materials for paths.

With the publication in the late 1960s and 1970s of the works of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the world became aware that the Soviet regime used camps (gulags) to repress dissidents who might be imprisoned for as much as twenty years. There were similarities with the Lager; the hard physical work and poor rations. Levi rejected, however, the idea that the Gulag Archipelago and the system of the Nazi Lager (German: Vernichtungslager; see Nazi concentration camps) were equivalent. The death rate in the gulags was estimated at 30% at worst, he wrote, while in the Lager he estimated it was 90-98%. The aim of the Lager was to eliminate the Jewish race. No one was excluded. No-one could renounce Judaism; the Nazis treated Jews as a racial group rather than a religious one. Many children were taken to the camps, and almost all died.The purpose of the Nazi camps was not the same as that of the Soviet gulags, Levi wrote in an appendix of If this is a Man, though it is a "lugubrious comparison between two models of hell".

Levi himself, along with most of Turin's Jewish intellectuals, was not religiously observant. It was the Fascist race laws and the Nazi camps that made him feel Jewish. Levi writes in clear almost scientific style about his experiences in Auschwitz, showing no lasting hatred of the Germans. This has led some commentators to suggest that he had forgiven them, though Levi denied this.

Death

Levi died on April 11, 1987, when he fell from the interior landing of his third-story apartment in Turin to the ground floor below. Elie Wiesel said at the time that "Primo Levi died at Auschwitz forty years earlier."

The coroner interpreted Levi's death as suicide, and three of his biographers (Angier, Thomson and Anissimov) agree with this interpretation. In his later life Levi indicated he was suffering from depression: factors may have included responsibility for his elderly mother and mother-in-law, living in the same apartment, concerns for his own health and memory, and genetic disposition.

However, Oxford sociologist Diego Gambetta has argued that the conventional assumption of Levi's death by 'suicide' is not well justified by either factual or inferred evidence. Levi left no suicide note, and no other clear indication that he had thoughts of taking his own life. In Gambetta's view, documents and testimony indicate immediate and ongoing plans at the time of his death. Rita Levi Montalcini, a close friend of Levi, commented that "If Levi wanted to kill himself he, a chemical engineer by profession, would have known better ways than jumping into a narrow stairwell with the risk of remaining paralyzed."

Also, Gambetta has pointed out that Levi had complained to his physician of dizziness in the days before his death, and concludes (from a visit to the apartment complex) that it is more plausible to assume Levi lost his balance and fell accidentally to his death. The matter remains unresolved.

More here.

Primo Michele Levi (31st July1919 to 11th April 1987) was a Jewish-Italian chemist, Holocaust survivor and author of memoirs, short stories, poems, essays and novels.

He is best known for his work on the Holocaust, and in particular his account of the year he spent as a prisoner in Auschwitz, the death camp in Nazi-occupied Poland. If This Is a Man (published in the United States as Survival in Auschwitz) has been described as one of the most important works of the twentieth century.

Early life

Levi was born in Turin on July 31, 1919 at Corso Re Umberto 75 into a liberal Jewish family. His father Cesare worked for the manufacturing firm Ganz and spent much of his time working abroad in Hungary, where Ganz was based. Cesare was an avid reader and autodidact. Levi’s mother Ester, known to everyone as Rina, was well educated, having attended the Instituto Maria Letizia. She too was an avid reader, played the piano and spoke fluent French. The marriage between Rina and Cesare was arranged by Rina’s father. On their wedding day, Rina’s father, Cesare Luzzati, gave Rina the apartment at Corso Re Umberto where Primo Levi was to live for almost his entire life.

In 1921 Anna Maria, Levi's sister was born; he was to remain close to her all of his life. In 1925 he entered the Felice Rignon primary school in Turin. A thin and delicate child, he was shy and thought of himself as being ugly, but he excelled academically. His school record includes long periods of absence during which time he was tutored at home at first by Emilia Glauda and then by Marisa Zini, daughter of philosopher Zino Zini. Summers were spent with his mother in the Waldensian valleys south-west of Turin where Rina rented a farmhouse. His father remained in Turin partly because of his dislike of the rural life, but also because of his infidelities.

In September 1930 he entered the Massimo d'Azeglio Royal Gymnasium a year ahead of normal entrance requirements. In class he was the youngest, the shortest and the cleverest as well as being the only Jew. For these reasons, he was bullied. In August 1932, following two years at the Talmud Torah school in Turin, he sang in the local synagogue for his Bar Mitzvah. In 1933, as was expected of all young Italian schoolboys, he joined the Avanguardisti movement for young Fascists. He avoided rifle drill by joining the ski division, and then spent every Saturday during the season on the slopes above Turin.

As a young boy Levi was plagued by illness, particularly chest infections, but he was keen to participate in physical activity. In his teens Levi and a few of his friends would sneak into a disused sports stadium and conduct athletic competitions.

In July 1934 at the age of 14, he sat the exams for the Massimo d'Azeglio liceo classico, a Lyceum (sixth form) specialising in the classics and was admitted that autumn. The school was noted for its well-known anti-Fascist teachers, amongst them the philosopher Norberto Bobbio, and for a few months Cesare Pavese, also an anti-Fascist and later to become one of Italy's best-known novelists. Levi continued to be bullied during his time at the Lyceum although he was now in a class with six other Jews. On reading Concerning the Nature of Things by Sir William Bragg it was during this time that Levi decided that he wanted to be a chemist. Levi matriculated from the school in 1937 despite being accused of ignoring a call-up to the Italian Royal Navy the week before his exams were due to begin. As a result of this incident, and possibly some antisemitic bias in the marking, Levi had to retake his Italian paper. At the end of the summer he passed his exams and in October he enrolled at the University of Turin, to study chemistry. The registered intake of eighty hopefuls spent three months taking lectures in preparation for their colloquio or oral examination when the eighty would be reduced to twenty. The following February Levi graduated onto the full-time chemistry course.

Although Italy was a Fascist country, and antisemitism took place, there was little real discrimination towards Jews in the 1930’s. As Italy was historically one of the most assimilated Jewish societies, the gentile Italians, up until the outbreak of hostilities, either ignored or subverted any racial laws which they saw as being imposed by the Germans. This all changed in July 1938 when the Fascist government introduced racial laws which, amongst other things, prohibited Jewish citizens from attending state schools. Jewish students who had begun their course of study were permitted to continue them, but new Jewish students were barred from entering university. It was therefore fortuitous that Levi had matriculated a year early, as he would not otherwise have been permitted to take a degree.

In 1939 Levi began his love affair with hiking in the mountains. His friend Sandro Delmaestro taught him how to hike and they spent many week-ends in the mountains above Turin. Physical exertion, the risk and the battle with the elements here supplied him with an outlet for all the frustrations in his life. In June 1940 Italy declared war against Britain and France, and the first air raids on Turin began two days later. Levi’s studies continued during the bombardments, and an additional strain on the family was imposed when his father became bedridden with bowel cancer.

However because of the new antisemitic laws, and the increasing intensity of prevalent Fascism, Levi had difficulty finding a supervisor for his graduation thesis which was on the subject of Walden inversion, a study of the asymmetry of the carbon atom. Eventually taken on by Dr. Nicolo Dallaporta he graduated in the summer of 1941 with full marks and merit, having submitted additional theses on X Rays and Electrostatic Energy. His degree certificate bore the remark, "of Jewish race". The racial laws prevented Levi from finding a suitable permanent position after he had graduated.

In December 1941 Levi was approached and clandestinely offered a job at an asbestos mine at San Vittore. The project he was given was to extract nickel from the mine spoil, a challenge he accepted with pleasure. It was not lost on Levi that should he be successful he would be aiding the German war effort, which was suffering nickel shortages in the production of armaments. The job required Levi to work under a false name with false papers. In March 1942 while he was working at the mine Levi’s father died.

In June 1942, due to the deteriorating situation in Turin, Levi left the mine and went to work in Milan. He had been recruited through a fellow student at Turin University who was now working for the Swiss firm of A Wander Ltd on a project to extract an anti-diabetic from vegetable matter. He could take the job because the racial laws did not apply to Swiss companies. It soon became clear that the project had no chance of succeeding, but it was in no one's interest to say so.

In September 1943, after the Italian government under Marshal Pietro Badoglio signed an armistice with the Allies, the former leader Benito Mussolini was rescued from imprisonment by the Germans and installed as head of the Italian Social Republic, a puppet state in German-occupied northern Italy. Levi returned home to Turin to find his mother and sister having taken refuge in their holiday home La Saccarello in the hills outside Turin. They all then embarked to Saint-Vincent in the Aosta Valley where they could be hidden. Being pursued by the authorities they moved up the hillside to Amay in the Colle di Joux. Amay was on the route to Switzerland that was followed by Allied soldiers and refugees trying to escape the Germans. The Italian resistance movement became increasingly active in the German-occupied zone. Levi and a number of comrades took to the foothills of the Alps and in October joined the liberal Giustizia e Libertà partisan movement. Completely untrained for such a venture, he and his companions were quickly arrested by the Fascist militia. When told he would be shot as a partisan, he confessed to being Jewish and was then sent to an internment camp for Jews at Fossoli near Modena. Primo Levi's writings archived at Yad Vashem indicate that that as long as Fossoli was under Italian, rather than Nazi German control, he was not harmed. "We were given, on a regular basis, a food ration destined for the soldiers," Levi's testimony stated, "and at the end of January 1944, we were taken to Fossoli on a passenger train. Our conditions in the camp were quite good. There was no talk of executions and the atmosphere was quite calm. We were allowed to keep the money we had brought with us and to receive money from the outside. We worked in the kitchen in turn and performed other services in the camp. We even prepared a dining room, a rather sparse one, I must admit."

Auschwitz

When Fossoli fell into the hands of the Germans, the Jews were rounded up for deportation. On February 21, 1944, the inmates of the camp were transported to Auschwitz in twelve cramped cattle trucks. Levi spent eleven months there before the camp was liberated by the Red Army. Of the 650 Italian Jews in his shipment, Levi was one of only twenty who left the camps alive. The average life expectancy of a new entrant was three months.

Levi knew some German from reading German publications on chemistry; he quickly oriented himself to life in the camp without attracting the attention of the privileged inmates; he used bread to pay a more experienced Italian prisoner for German lessons and orientation in Auschwitz; and he received a smuggled soup ration each day from Lorenzo Perrone, an Italian civilian bricklayer, imprisoned as forced labourer. His professional qualifications were also useful: in mid-November 1944 he was able to secure a position as an assistant in the Buna laboratory that was intended to produce synthetic rubber, thereby avoiding hard labour in freezing outdoor temperatures.

Shortly before the camp was liberated by the Red Army, he fell ill with scarlet fever and was placed in the camp's sanatorium (camp hospital). In mid-January 1945 the SS hurriedly evacuated the camp as the Red Army approached, forcing all but the gravely ill on a long death march that led to the death of the vast majority of the remaining prisoners. Levi's illness spared him this fate.

Although liberated on 27 January 1945, Levi did not reach Turin until 19 October of that year. After spending some time in a Soviet camp for former concentration camp inmates, he embarked on an arduous journey home in the company of former Italian prisoners of war from the Royal Italian Army in Russia. His long railway journey home to Turin took him on a circuitous route from Poland, through Russia, Romania, Hungary, Austria and Germany.

What drove Levi to write was a desire to bear witness to the horrors of the Nazis' attempt to exterminate the Jewish people. He read many accounts of witnesses and survivors and attended meetings of survivors, becoming in the end a symbolic figure for anti-fascists in Italy.

Levi visited over 130 schools to talk about his experiences in Auschwitz. He was shocked by revisionist attitudes that tried to rewrite the history of the camps as less horrific, what is now referred to as Holocaust denial. His view was that the Nazi death camps and the attempted annihilation of the Jews was a horror unique in history because the aim was the complete destruction of a race by one that saw itself as superior; it was highly organized and mechanized; it entailed the degradation of Jews even to the point of using their ashes as materials for paths.

With the publication in the late 1960s and 1970s of the works of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the world became aware that the Soviet regime used camps (gulags) to repress dissidents who might be imprisoned for as much as twenty years. There were similarities with the Lager; the hard physical work and poor rations. Levi rejected, however, the idea that the Gulag Archipelago and the system of the Nazi Lager (German: Vernichtungslager; see Nazi concentration camps) were equivalent. The death rate in the gulags was estimated at 30% at worst, he wrote, while in the Lager he estimated it was 90-98%. The aim of the Lager was to eliminate the Jewish race. No one was excluded. No-one could renounce Judaism; the Nazis treated Jews as a racial group rather than a religious one. Many children were taken to the camps, and almost all died.The purpose of the Nazi camps was not the same as that of the Soviet gulags, Levi wrote in an appendix of If this is a Man, though it is a "lugubrious comparison between two models of hell".

Levi himself, along with most of Turin's Jewish intellectuals, was not religiously observant. It was the Fascist race laws and the Nazi camps that made him feel Jewish. Levi writes in clear almost scientific style about his experiences in Auschwitz, showing no lasting hatred of the Germans. This has led some commentators to suggest that he had forgiven them, though Levi denied this.

Death

Levi died on April 11, 1987, when he fell from the interior landing of his third-story apartment in Turin to the ground floor below. Elie Wiesel said at the time that "Primo Levi died at Auschwitz forty years earlier."

The coroner interpreted Levi's death as suicide, and three of his biographers (Angier, Thomson and Anissimov) agree with this interpretation. In his later life Levi indicated he was suffering from depression: factors may have included responsibility for his elderly mother and mother-in-law, living in the same apartment, concerns for his own health and memory, and genetic disposition.

However, Oxford sociologist Diego Gambetta has argued that the conventional assumption of Levi's death by 'suicide' is not well justified by either factual or inferred evidence. Levi left no suicide note, and no other clear indication that he had thoughts of taking his own life. In Gambetta's view, documents and testimony indicate immediate and ongoing plans at the time of his death. Rita Levi Montalcini, a close friend of Levi, commented that "If Levi wanted to kill himself he, a chemical engineer by profession, would have known better ways than jumping into a narrow stairwell with the risk of remaining paralyzed."

Also, Gambetta has pointed out that Levi had complained to his physician of dizziness in the days before his death, and concludes (from a visit to the apartment complex) that it is more plausible to assume Levi lost his balance and fell accidentally to his death. The matter remains unresolved.

More here.